Curl

Curl is defined on Wikipedia as “one of the first-order derivative operators that maps a 3-dimensional vector field to another 3-dimensional vector field.” While this definition may be mathematically accurate, it is difficult for anyone encountering it for the first time to fully comprehend.

In the author’s perspective, a more intuitive mathematical definition of Curl would be as follows, although it may not be a rigorous mathematical definition: “Curl is an operator that measures the extent of rotation of a small region in a vector field caused by the surrounding vectors at an arbitrary point.”

Another way to think about Curl is as “the change in the direction perpendicular to the normalized direction of the vector field at an arbitrary point $(x, y)$.”

Example of Curl: Stick on a River

Since the concept of Curl is slightly more difficult than Divergence, let’s start with a very simple example to better understand it.

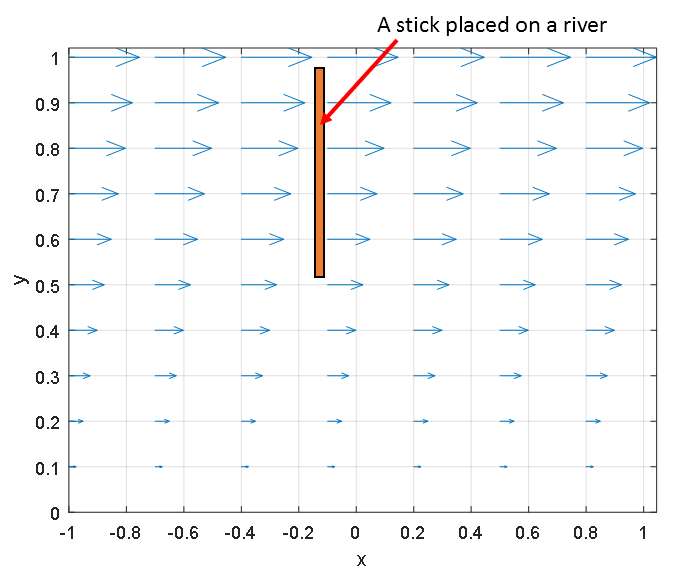

Figure 1: Stick placed on a river with arrows representing the velocity of the river flow.

Figure 1 shows a stick placed in a flowing river, where each arrow represents the velocity of the river flow. In other words, the vector function of the vector field represented in Figure 1 is

\[f(x, y) = y\hat{i}\]For now, it is not important to understand the specific function of the vector field. Let’s try to intuitively understand what Curl is trying to convey.

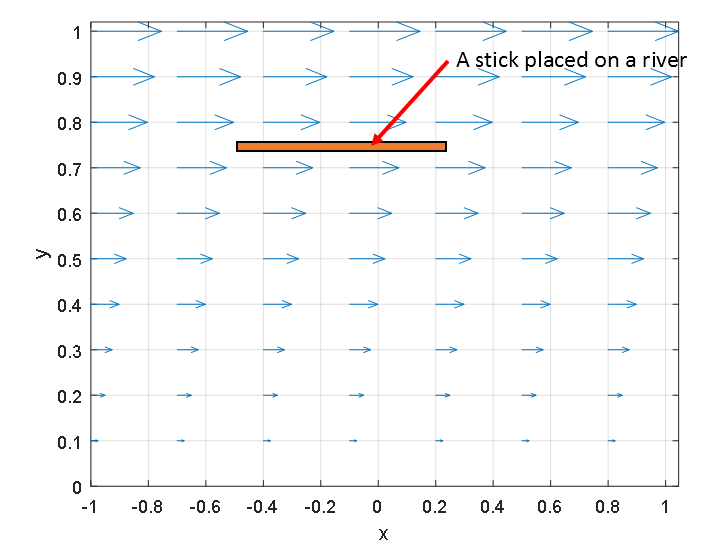

Since the stick receives different velocities at different parts, it will rotate clockwise. However, if the stick is placed in the same direction as the velocity of the flow, as shown in Figure 2, will it rotate? No, it won’t.

Figure 2: Stick placed horizontally in the direction of river flow does not rotate.

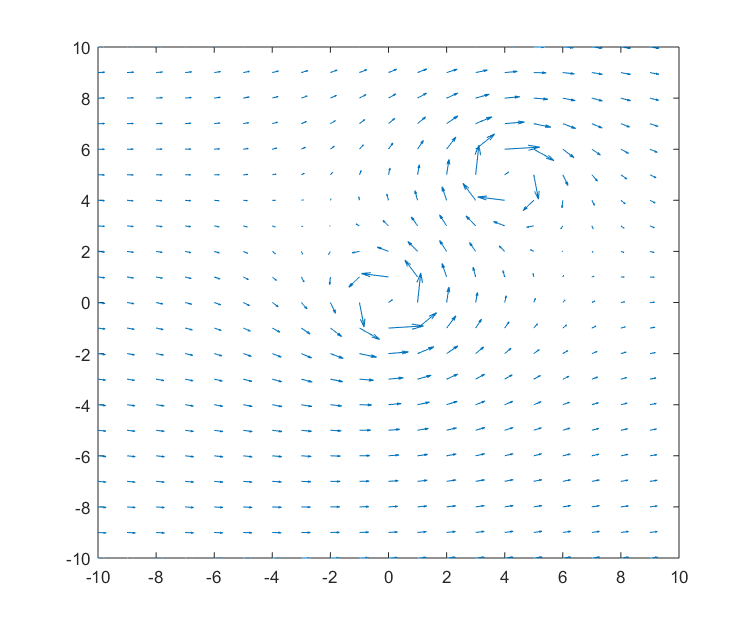

Example 2 of using curl: Eddies in River

Let’s consider another example where curl can be used, which is eddies or whirlpools on the surface of a river.

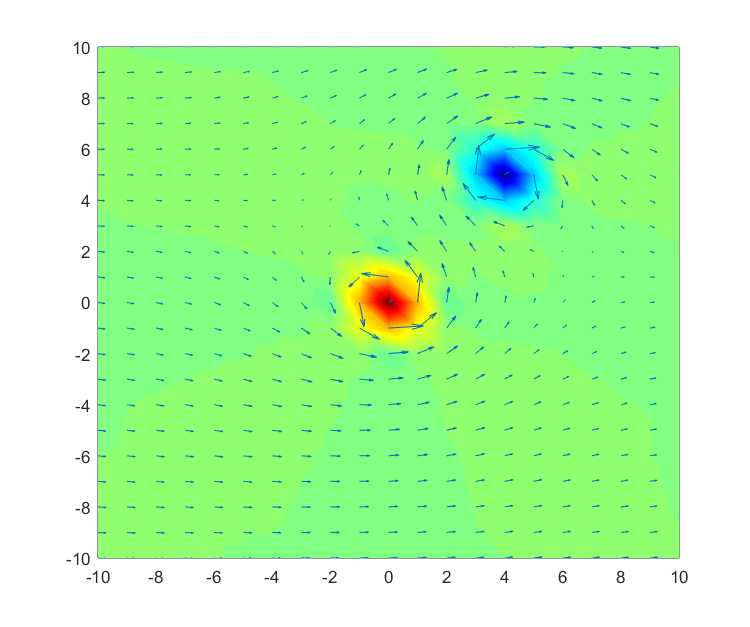

As seen in Figure 3 below, there are eddies forming at (0,0) and (4,5).

In curl, one important concept is the direction of rotation, and we can observe that the direction of rotation is different for the two eddies.

The eddy formed at (0,0) is rotating counterclockwise, while the eddy formed at (4,5) is rotating clockwise.

Figure 3: Eddies forming at specific points in a river

If we place particles on the river surface, we can observe that the particles rotate at the locations where the eddies are formed, as shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Movement of particles in a river with eddies

Using curl, we can quantify the rotational force at each position, even when the rotational forces are different at different points, as shown in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Quantification of rotational forces at all points in a river. Red indicates positive values, blue indicates negative values, and green indicates areas with rotational forces close to zero.

Curl represents rotational forces on infinitesimal areas

Similar to divergence, curl also represents the rotational forces on infinitesimal areas.

When looking at the micro level rather than the macro level, there are infinitely many vectors sticking to an arbitrary stick, as we have seen when studying divergence. Therefore, understanding how much rotation an infinitesimal area receives from the surrounding vectors is a similar context. Now, let’s consider mathematically how curl represents the rotational forces on infinitesimal areas.

Derivation of the Curl Formula

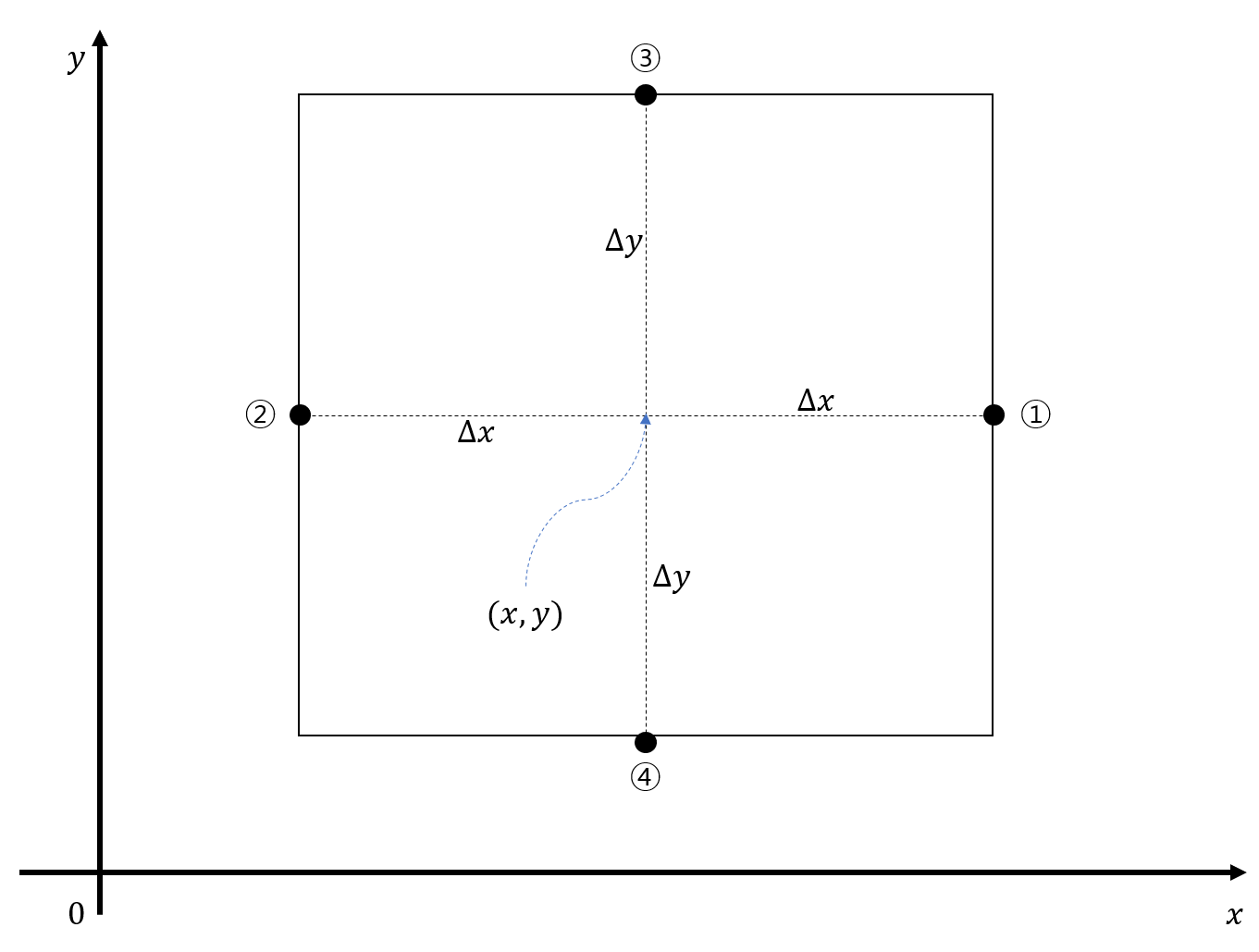

Let’s consider a small area as shown below. The center coordinates of this small area are $(x, y)$, and its width is $2\Delta x$ and height is $2\Delta y$. We will name the midpoints of the sides as ①, ②, ③, and ④, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 6: Small area on the xy-plane

Now we want to find the amount of rotation that this small area undergoes. In mathematics, counterclockwise direction is considered as the positive direction of rotation. However, to account for the clockwise direction of rotation, we need to consider both cases.

These are the rotations caused by the forces acting on the bar ①-② and the bar ③-④, respectively.

When the bar ①-② rotates, we can assume that there is no change in width of $2\Delta y$, and when the bar ③-④ rotates, we can assume that there is no change in width of $2\Delta x$. Therefore, we will superimpose the rotations obtained from these two cases to account for the two rotations.

Rotation is represented as a vector because it has a direction, and vectors can be combined using the principle of superposition.

Thus, the derivation can be divided into two steps. From now on, let’s assume that a vector field $f(x, y) = P(x, y)\hat{i} + Q(x, y)\hat{j}$ is formed on the xy-plane. Also, let’s assume that the rotation direction of the small area is counterclockwise.

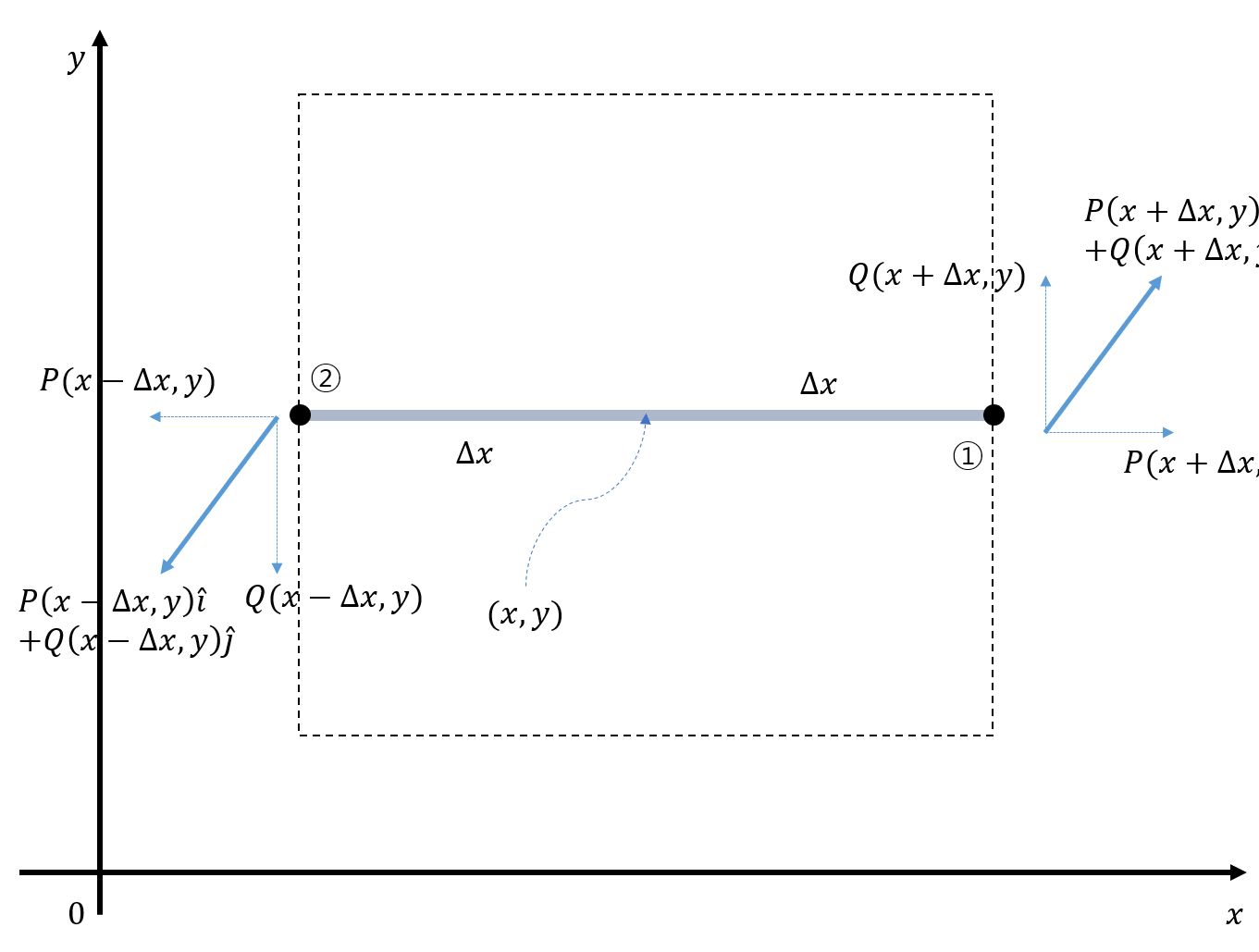

I) Rotation of the bar ①-②

Figure 7: Diagram showing the vectors acting on points ① and ② when the bar ①-② rotates

Let’s assume that the vector field $f(x,y)$ represents a force.

To consider only the torque received by the bar ①-② when it rotates, as shown in Figure 7,

we need to consider the net force acting on points ① and ②. Therefore, the net force that the bar ①-② receives to rotate is given by

\[Q(x+\Delta x, y) - Q(x-\Delta x, y)\]Then, the torque per unit length that the bar ①-② receives, since the length of the bar is $2\Delta x$, is

\[\frac{Q(x+\Delta x, y) - Q(x-\Delta x, y)}{2\Delta x}\]In the assumption, this length represents an infinitesimally small length, so $\Delta x$ should be taken very small.

Therefore, the torque per unit length that the bar ①-② receives for an infinitesimally small length is

\[\lim_{\Delta x \rightarrow 0}\frac{Q(x+\Delta x, y) - Q(x-\Delta x, y)}{2\Delta x} = \frac{\partial Q}{\partial x}\]At this point, we assumed that the direction of rotation is counterclockwise and the axis of rotation is in the $\hat{k}$ direction. Therefore, the vector that represents the rotation of the bar ①-② is

\[\frac{\partial Q}{\partial x}\hat{k}\]II) Rotation amount of the bar ③-④

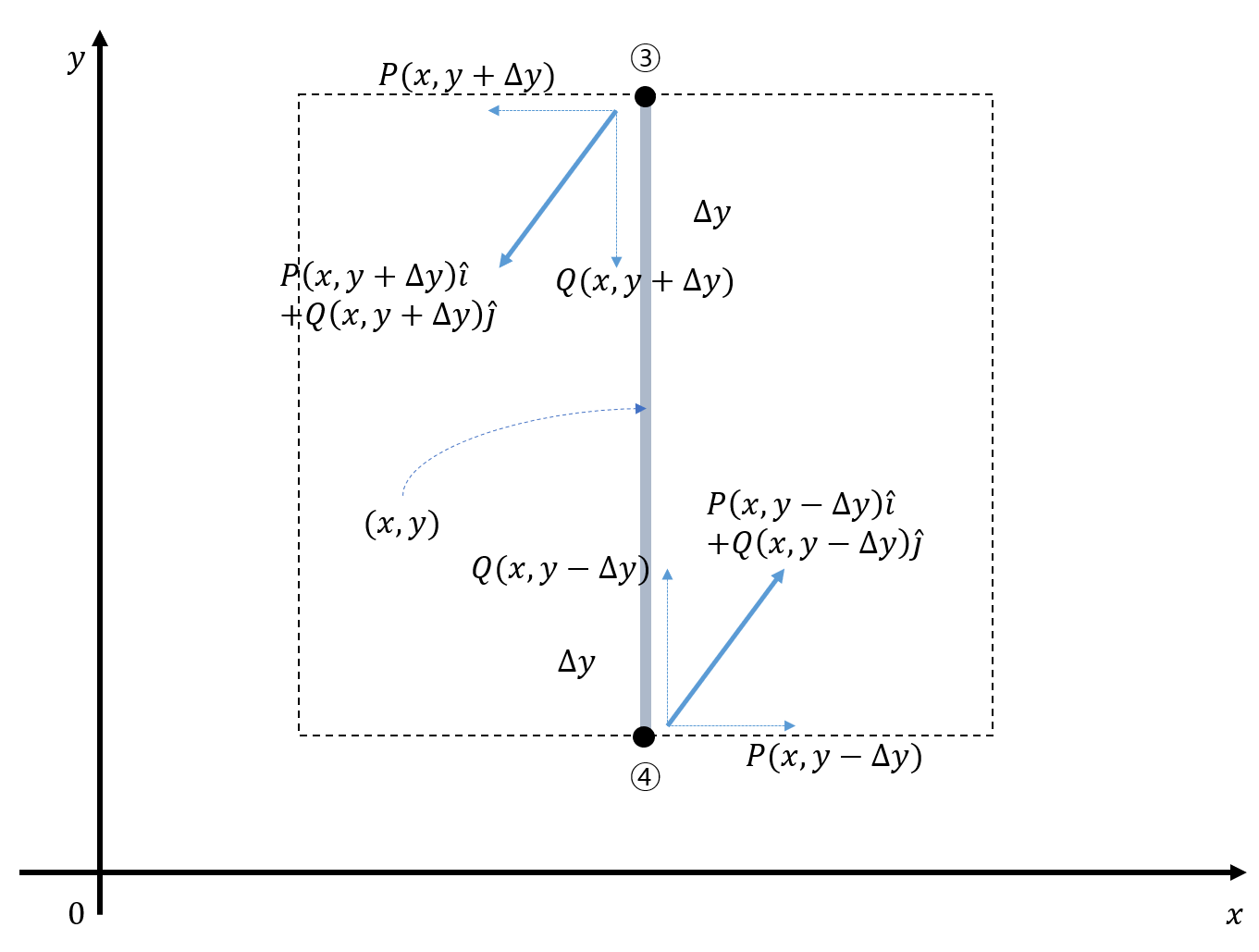

Figure 8: Diagram showing the vectors acting on points ③ and ④ when the bar ③-④ rotates

If a vector field $f(x,y)$ represents a force, to consider only the torque that the rod ③-④ receives when it rotates, as seen in Figure 8, we need to consider the net force in the direction of points ③ and ④.

Also, assuming that the rod rotates counterclockwise, taking that into consideration, the net force that the rod ③-④ receives for rotation is

\[P(x, y-\Delta y) - P(x, y+\Delta y)\]since the length of the rod ③-④ for a unit length is $2\Delta y$, the torque received by the rod for a unit length will be

\[\frac{P(x, y-\Delta y) - P(x, y+\Delta y)}{2\Delta y}\]In this assumption, the length represents an infinitesimal length, so $\Delta y$ should be taken very small.

Therefore, the total sum of the torque vectors that the infinitesimal area receives from the vectors acting on points ①, ②, ③, ④, according to I) and II), is

\[\left(\frac{\partial Q}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial P}{\partial y}\right)\hat{k}\]If you want to calculate the curl of an infinitesimal volume in 3-dimensional space, you can follow the same method in the yz plane and zx plane. If the vector field is represented as $f(x,y,z)=P(x,y,z)\hat{i}+Q(x,y,z)\hat{j}+R(x,y,z)\hat{k}$, then the value is

\[curl(f) = \left(\frac{\partial}{\partial y}R - \frac{\partial}{\partial z}Q \right)\hat{i} -\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}R - \frac{\partial}{\partial z}P \right)\hat{j} +\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}Q - \frac{\partial}{\partial y}P \right)\hat{k}\]As a professional math blogger, I would translate the sentences as follows:

This can also be expressed using the determinant of a 3-dimensional vector as follows:

\[\text{curl}(f) = \begin{vmatrix} \hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \\ P & Q & R \\ \end{vmatrix}\]This notation allows us to represent it using the del operator as well:

\[\text{curl}(f) = \begin{vmatrix} \hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \\ P & Q & R \\ \end{vmatrix} = \nabla \times f\]By looking at it this way, we can understand that the meaning of $\nabla \times f$ is the rate of change in the direction perpendicular to the normalized direction in which the vector field points, at any arbitrary point $(x, y)$.