이 문서의 한국어 버전은 아래의 위치에서 찾을 수 있습니다. (You can find a Korean version of this article as below.)

1. Degree Measurement System (base 60 System)

The base 60 system is a way of dividing the right angle into 90 equal parts. It was invented to make it easier to handle triangles.

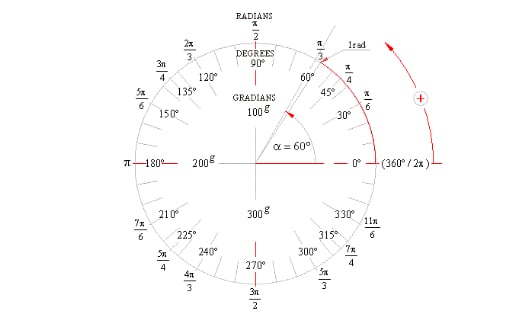

Since we were young, or even in our daily lives, the most commonly used method of measuring angles is the base 60 system. The base 60 system is a way of dividing the right angle into 90 equal parts. I think it is called the base 60 system because this system follows the base 60 numeral system, which calls the subunits of degree, minute, and second. For example, 1/60 degree is called 1 minute, and 1/60 minute is called 1 second.

But why did we define dividing the right angle into 90 parts as 1 degree? There are several explanations, but I think it is an idea invented to make it easier to handle triangles. In cultures that use the decimal system, using numbers such as 10, 100, 1000 as a “basis” is useful. It’s like defining the boiling point of water as 100 degrees. In that sense, it can be a very reasonable choice to define the right angle as 100 degrees. In fact, there is an angle system called the gradian, which divides the right angle into 100 parts1.

Living in a culture that uses the decimal system, the gradian system can be intuitive, but it can be difficult to analyze shapes. Let’s think of a regular triangle. As commonly known, in the base 60 system that we commonly use, the size of one angle of a regular triangle is 60 degrees. What if we apply the gradian system? It becomes 66.67 degrees. Understanding polygons is important to understand shapes. Therefore, I think that the reason we adopted the base 60 system in mathematics is that we defined one angle of a triangle as the closest number that is also a multiple of 60 with many factors, rather than 66.67 degrees, to make it easier to analyze plane shapes.

2. Radian

Radian and degree measurements differ in the way they interpret angles. Radian comes from the word “radius,” which refers to the radius of a circle.

The difference between degree and radian lies in the observation point when the circle is drawn. Let’s imagine drawing a circle. Degree measurement quantifies the angle by looking at how much your head tilts up from the center of the circle during the drawing process. On the other hand, radian looks at how much the pencil has traveled in relation to the radius of the circle. The distance the pencil travels is called an “arc,” and radian is a system that uses the length of an arc to measure angles.

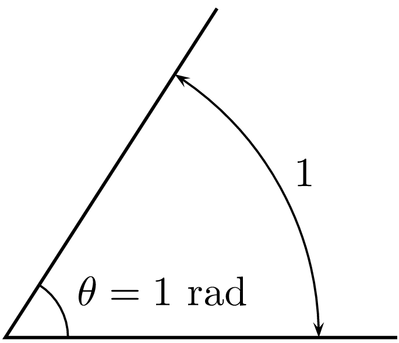

In general, 1 radian is defined as follows:

One radian is a dimensionless unit that corresponds to the size of the central angle that corresponds to an arc length equal to the length of the radius on the circumference of a circle. More generally, the value of a radian is equal to the ratio of the length of the arc to the radius of the circle. That is, θ = s / r, where θ is the angle given in radians, s is the length of the arc, and r is the radius. (source: Wikipedia)

Radian is more logical and mathematical because it makes good use of the mathematical properties of a circle. A circle always has a constant ratio between the diameter and the circumference. That is, no matter what the size of the circle is, the radius and the circumference of the circle always have a ratio of $2\pi$. Therefore, the radian system is a system that reflects the characteristics of a circle well.

3. Why use trigonometry instead of radians?

The most important reason for using trigonometry instead of radians is related to the differentiation of trigonometric functions. To put it simply, we use trigonometry to get clean results when we differentiate trigonometric functions. Let’s take a look at the differentiation of the sine function.

\[\frac{d}{dx}\sin(x) = \lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{\sin(x+h)-\sin(x)}{h}\] \[\Rightarrow \lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{\sin(x)\cos(h)+\cos(x)\sin(h)-\sin(x)}{h}\]Here, since $\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\cos(h)=1$,

\[\Rightarrow \lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{\sin(x)-\sin(x)+\cos(x)\sin(h)}{h}=\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{\cos(x)\sin(h)}{h}\] \[=\cos(x)\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\]Now, let’s think about what would be happen to $\lim_{h\to 0}{\sin(h) \over h}$ (squeeze theorem).

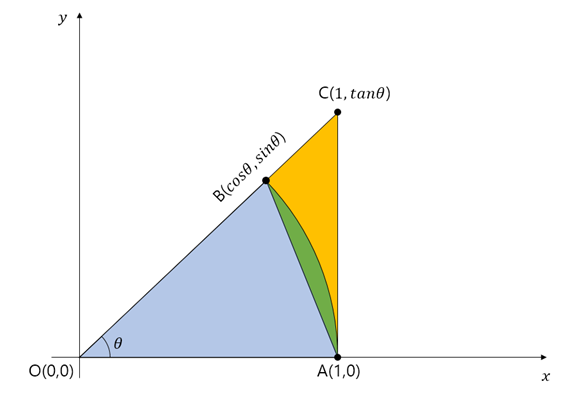

If you think about the area of the regions marked in blue, green, and yellow in the picture below, the area is always in the order of blue, green, and yellow. To express it in a formula, the green area is the area of the sector with a length of 1 and an angle of $\theta$.

Now, let’s describe the areas of the blue, green, and yellow sections mathematically, separately for the case of using angle measurement and the case of using the trigonometric functions.

➀ When using degrees

The relationship between the areas of the blue, green, and yellow regions can be expressed as follows:

\[\frac{1}{2}\times 1 \times \sin(\theta °) \leq \pi \times 1^2 \times \frac{\theta °}{360 °}\leq \frac{1}{2}\times 1 \times \tan(\theta °)\]In other words,

\[\frac{\sin(\theta °)}{2}\leq \pi \frac{\theta °}{360 °}\leq \frac{\tan(\theta °)}{2}\]If you multiply 360 degree in both sides and divide by $\pi$, we get:

\[\frac{360 °}{\pi}\times \frac{\sin(\theta °)}{2}\leq \theta °\leq \frac{360 °}{\pi}\times\frac{\tan(\theta °)}{2}\]Let’s divide the both side by $\sin(\theta °)$:

\[\frac{180 °}{\pi}\leq\frac{\theta °}{\sin(\theta °)}\leq\frac{180 °}{\pi}\times\frac{1}{\cos(\theta °)}\]Now, we can flip the numerator and denominator,

\[\frac{\pi}{180 °}\geq \frac{\sin(\theta °)}{\theta}\geq\frac{\pi}{180 °}\times \cos(\theta °)\]Hence, when $\theta °$ becomes to $0$,

\[\frac{\sin(\theta °)}{\theta °}\]converges to

\[\frac{\pi}{180 °}\]➁ When using radians,

Similarly, we can also express the relationship between the areas of the blue, green, and yellow regions using radians.

\[\frac{1}{2}\sin(\theta)\leq \pi \frac{\theta}{2\pi}\leq \frac{1}{2}\tan(\theta)\]In other words,

\[\frac{\sin(\theta)}{2}\leq \frac{\theta}{2}\leq \frac{\tan(\theta)}{2}\]Let us multiply 2 in both sides and divide them with $\sin (\theta)$.

\[1\leq \frac{\theta}{\sin(\theta)}\leq \frac{1}{\cos(\theta)}\]Now, we can flip the numerator and denominator,

\[1\geq \frac{\sin(\theta)}{\theta} \geq \cos(\theta)\]Hence, when $\theta \to 0$,

\[\frac{\sin\theta}{\theta}\]converges to

\[1\]Again, back to trigonometry.

Again, let’s express eq (4) with both degrees and radians.

➀ with “degrees”,

\[\frac{d}{dx}\sin(x)=\cos(x)\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\] \[=\cos(x)\times \frac{\pi}{180°}\]➁ with “radians”,

\[\frac{d}{dx}\sin(x) = \cos(x) \lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\] \[=\cos(x)\]Hence, using the radians has the advantage of making trigonometric differentiation neater and more straightforward.

-

CalculateMate.com https://www.calculatemate.com/calculators/angle/degrees-to-gons ↩