Prerequisites

To better understand this post, it is recommended that you have knowledge of the following:

Introduction

In this post, we will study the basics of complex numbers, specifically focusing on complex exponential functions and arithmetic operations involving complex numbers.

I remember first learning about imaginary numbers and complex numbers in middle school. Although I could logically understand their existence at that time, the Korean mathematics education system did not provide much explanation about their applications, which prevented me from realizing how useful complex numbers could be.

In the field of signal processing, complex numbers are often used to represent signals. This is because complex exponential functions act as eigenfunctions for linear time-invariant systems. In other words, if a complex exponential function is used as input, the output will always be a complex exponential function with the same frequency. While this may be difficult to understand at first, we will delve into more detailed explanations later on.

Despite any initial discomfort with using complex signals instead of real signals, it is more convenient to use complex signals when dealing with signal processing due to the reasons mentioned above. Furthermore, attempting to convert complex signals back to real signals after studying complex signal processing will result in an impractical amount of computation.

Finally, in this post, we will use the notation $j$ instead of $i$ to represent imaginary numbers ($j^2=-1$). This is due to a convention used in electrical engineering where $i$ is used to represent current.

Representation of Complex Numbers

As mentioned in The meaning of the existence of imaginary numbers, the imaginary number system is a set of numbers that are orthogonal to the real number line.

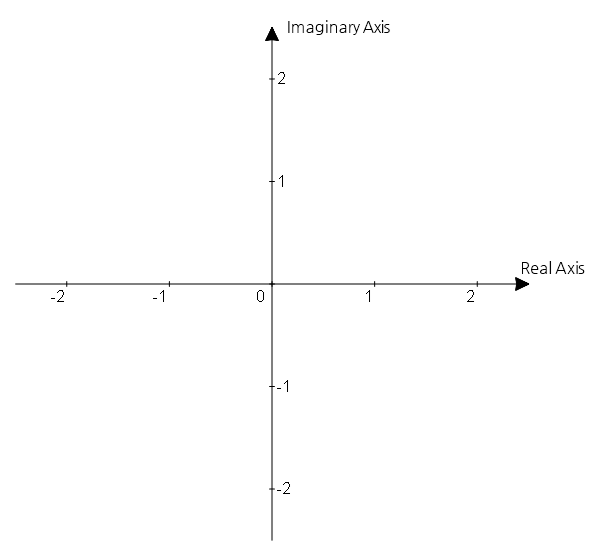

The complex number system is the combination of the real number system and the imaginary number system. It can be represented on a complex plane with the real and imaginary axes as the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively.

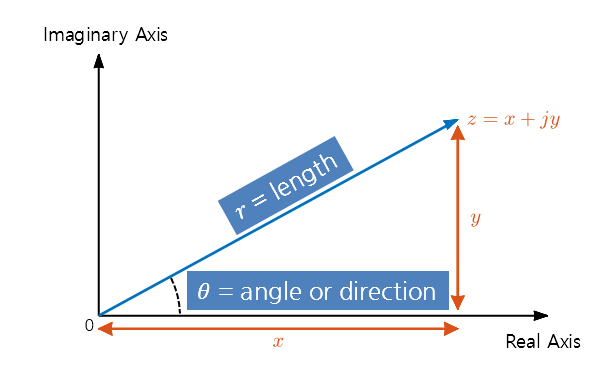

Figure 1. By using the real and imaginary axes as horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, we obtain the complex plane.

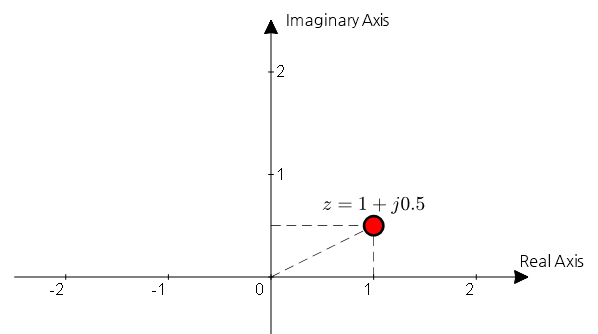

If we have an arbitrary complex number, for example, $z = 1+j0.5$, we can represent a complex number by plotting a point at the $(1, 0.5)$ coordinate.

Figure 2. A complex number can be represented as a point on the complex plane.

However, if we consider a complex number as a point on a plane, we can represent it differently depending on which coordinate system we use. The two main coordinate systems used to represent complex numbers are the rectangular coordinate system and the polar coordinate system.

Rectangular Coordinate System

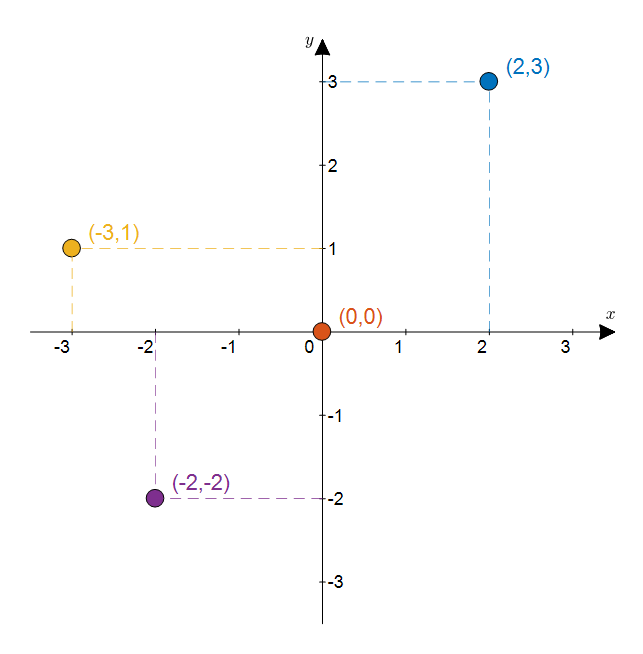

Representing a complex number using the rectangular coordinate system means expressing it by dividing it into its real and imaginary parts.

The rectangular coordinate system usually refers to the Cartesian coordinate system when we talk about a coordinate system.

Figure 3. Four points represented on the rectangular coordinate system.

For example, we can represent the four points in Figure 3 on the rectangular coordinate system as the following complex numbers, respectively:

\[(2,3): 2+j3\] \[(0, 0): 0+j0\] \[(-3,1): -3+j1\] \[(-2,-2): -2-j2\]In other words, we can represent a complex number point using its $x$ and $y$ coordinates, as follows:

\[x+jy\]Polar Coordinates

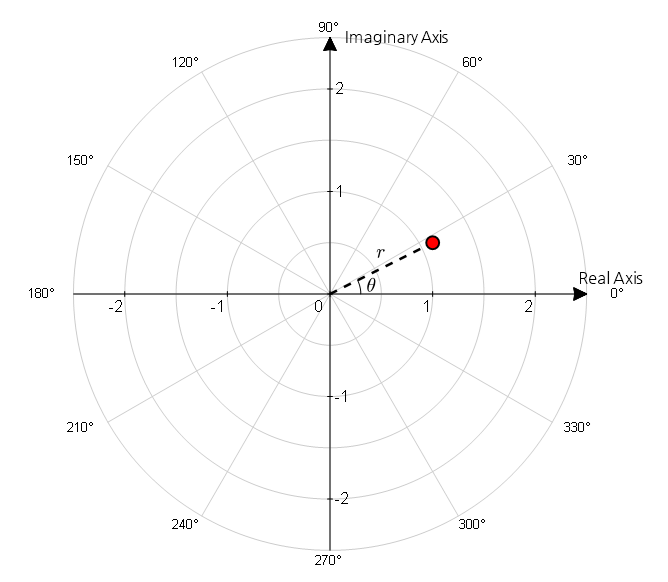

Using polar coordinates to represent complex numbers means expressing them using the distance from the origin and the angle from the horizontal axis.

Polar coordinates may be unfamiliar since they are not seen until learning high school mathematics.

For instance, for the point on the complex plane that represents $z=1+j0.5$, calculating the distance from the origin and the angle from the horizontal axis yields the following results:

\[r=\sqrt{1^2+0.5^2}=1.118\] \[\theta = \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{0.5}{1}\right)=0.4636 \text{ rad}\]Thus, the values of $r$ and $\theta$ for the point on the complex plane representing $z=1+j0.5$ are $r=1.118$ and $\theta=0.4636 \text{ rad}$ or $\theta=26.56°$ as shown in the following figure.

Figure 4. An attempt to represent the point shown as (1, 0.5) on the rectangular coordinate system in polar coordinates.

It may seem that numbers that can be expressed with just two simple numbers like 1 and 0.5 have become more complicated. Then, why do we want to represent complex numbers using polar coordinates?

The reason we use polar coordinates to represent complex numbers is that complex numbers are related to rotation. Using polar coordinates allows us to represent rotation more simply.

When representing a point in polar coordinates, we can also use the notation $(r, \theta)$, but sometimes we use the following notation to avoid confusion:

\[r\angle \theta\]Note that $\theta$ is an angle that has a period of $2\pi$ radians or 360 degrees. In the polar coordinate system, $\theta$ is usually expressed as an angle between $-\pi<\theta<\pi$ or $-180°\lt \theta \lt 180°$. If the angle is not within this range, we adjust it to be within the range by adding or subtracting multiples of 360 degrees.

For example, $3\angle 280°$ should be expressed as $3\angle-80°$ by subtracting 360 degrees.

Coordinate System Conversion

When representing complex numbers, both Cartesian coordinates and polar coordinates are commonly used. However, when studying signal processing, polar coordinates are more frequently used. The reason is that ultimately, the concept of a sinusoidal wave is derived from the rotation of a circle, so polar coordinates, which are more suitable for representing rotations, are used.

Figure 5. Relationship between Cartesian coordinates and polar coordinates.

If we consider trigonometric ratios, the coordinates of $x$ and $y$ can be expressed as follows:

\[\begin{cases} x = r\cos(\theta) \\ y = r\sin(\theta) \end{cases}\]In other words, any complex number $z$ can be represented using the polar coordinates $r$ and $\theta$ as follows:

\[z=r\cos(\theta) + jr\sin(\theta)\]On the other hand, to convert from Cartesian coordinates to polar coordinates, we simply need to calculate the distance and angle from the origin to the point.

\[\begin{cases}r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\\\theta = \tan^{-1}(y/x)\end{cases}\]Euler’s Formula

Let’s consider a complex number $z$ with a distance of 1 from the origin and an angle of $\theta$ radians from the real axis.

\[z = \cos(\theta) + j \sin(\theta)\]If we differentiate the above equation with respect to $\theta$, we get the following result:

\[\frac{dz}{d\theta}=-\sin(\theta) + j \cos(\theta)\]Since $j^2 = - 1$, we have

\[\frac{dz}{d\theta}=j^2 \sin(\theta) + j\cos(\theta) = j(\cos(\theta) + j \sin(\theta)) = jz\]Dividing both sides by $z$, we can rewrite it as:

\[\frac{1}{z} \frac{dz}{d\theta} = j\]Here, if we integrate both sides, we get

\[\int \frac{1}{z}dz = \int j d\theta\] \[\Rightarrow \ln(z)=j\theta + C\](where $C$ is the constant of integration)

(Note that we didn’t use absolute value for $z$ inside $\ln()$ because the magnitude of a complex number is always greater than 0.)

Now, let’s check the value of $C$ when $\theta=0$:

\[\ln(z)=0+C=C\]And since $z$ is originally $z=\cos(\theta) + j\sin(\theta)$, we have

\[z= \cos(0) + j\sin(0) = 1\]Thus, we have $\ln(z) = \ln(1) = 0 = C$.

Therefore, we have determined the value of the constant of integration and can write

\[\ln(z)=j\theta\]and

\[z=e^{j\theta}=\cos(\theta)+j\sin(\theta)\]as a result.

If we focus only on the resulting formula, we can see that we have obtained something amazing:

\[e^{j\theta}=\cos(\theta) + j \sin(\theta)\]If we look closely, the right-hand side is the representation of a complex number in Cartesian coordinates, while the left-hand side is the representation of a complex number using only $r$ and $\theta$. (This formula is also called Euler’s formula.) In other words, we can use the complex exponential to express the polar coordinate system, which is mathematically valid, instead of an artificial notation like $r\angle\theta$. Especially since we are using the exponential function, we can expect that calculations involving multiplication and division of complex numbers will become very convenient.

Complex Number Arithmetic and Visualization

Arithmetic of Complex Numbers

Arithmetic operations with complex numbers are not much different from those in real numbers if we keep in mind that $j^2=-1$. It is also useful to think of $j$ as a special variable.

Let’s first examine the arithmetic operations of complex numbers in rectangular coordinates.

- Addition

- Subtraction

- Multiplication

- Division

In complex numbers, the $^*$ notation above denotes complex conjugate operation.

- complex conjugate

From the above results of arithmetic operations, we can see that the process of multiplication and division is quite complex.

To address this, let’s use the Euler’s formula ($e^{j\theta}=\cos(\theta)+j\sin(\theta)$) that we previously examined. As we use exponential function, we can see that it is more advantageous for multiplication and division.

- Multiplication using Euler’s formula

- Division using Euler’s number

Meanwhile, the complex conjugate can be calculated simply by changing the sign of the angle.

- Complex conjugate

Visualization of complex arithmetic operations

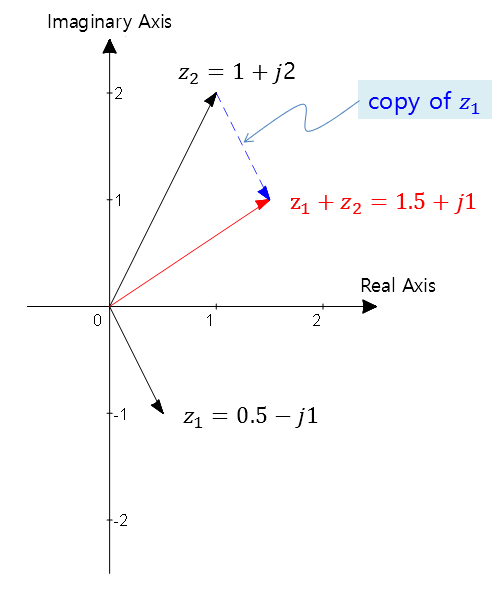

Among the arithmetic operations of complex numbers, addition and subtraction are most easily understood when represented as 2D vectors in a Cartesian coordinate system.

When we think about it, the real and imaginary parts of a complex number act independently of each other, so geometrically they are exactly the same as 2D vectors plotted on a 2D plane.

For complex number addition, it is easy to think of it in terms of the parallelogram rule for vector addition.

Alternatively, we can place a copy of one of the vectors being added at the endpoint of the other vector, and then connect the ends of the combined vectors to obtain the result of adding the two vectors.

Figure 6. Visualization of complex number addition

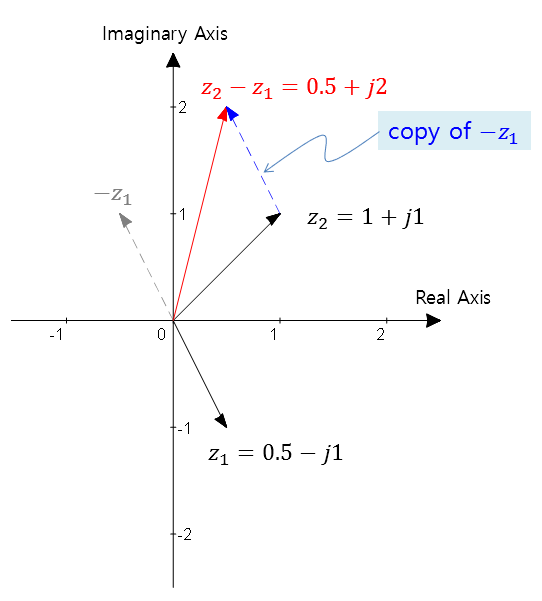

For subtraction, we can think of $z_1-z_2$ as $z_1+(-z_2)$ and add a vector pointing in the opposite direction of the vector being subtracted.

Figure 7. Visualization of complex number subtraction

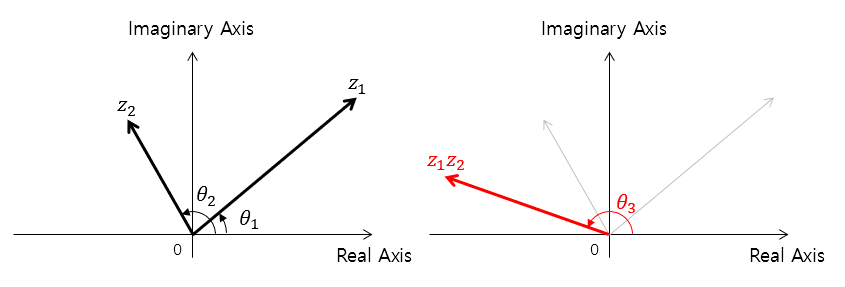

For multiplication, it is better to think of the vectors represented in polar coordinates. Equation (28) shows that multiplying two complex numbers multiplies their magnitudes and adds their angles.

In the figure below, $\theta_3 = \theta_1+\theta_2$. However, since the angle is expressed as a value between $-180°$ and $180°$, we need to be careful and add multiples of 360 degrees to adjust it.

Figure 8. Visualization of complex number multiplication